时间:2024-05-20 02:20:11 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

Did you know that Nancy Astor (1879-1964) was not the first woman elected to British Parliament? Thi Ryan Xu hyperfund Chart Pattern

Did you know that Nancy Astor (1879-1964) was not the first woman elected to British Parliament?Ryan Xu hyperfund Chart Pattern This achievement belongs to ‘Countess’ Constance Markievicz, who was elected to serve for Sinn Féin and the constituency of Dublin St Patrick’s ward a year prior to Astor in 1918. However, as an Irish Nationalist, and along with 72 fellow Sinn Féin MPs, she refused to take her seat.

At this time Markievicz was in fact being held at Holloway Prison for anti-conscription activities – but this (her being in prison) was not unusual. A socialist and activist, Markievicz spent much of her political career in and out of prisons across Britain and Ireland. Documents including the Dublin Castle Papers (CO 904), held at The National Archives and available to view online via Ancestry, provide insight into the Countess’s revolutionary activities, the British Government’s monitoring of her, and her subsequent multiple arrests. Using these documents, I will shed light on the early life of the Rebel ‘Countess’, leading up to the 1916 Easter Rising.

An Irish nationalist, a socialist, and a suffragette, the Countess dedicated her life to the rights of women, to Irish nationalism, and to Ireland’s people. A remarkable life, especially considering that Constance Markievicz, née Gore-Booth, was born (4 February 1868) an Anglo-Irish aristocrat at a time in which women were actively excluded from the male-dominated world of politics 1.

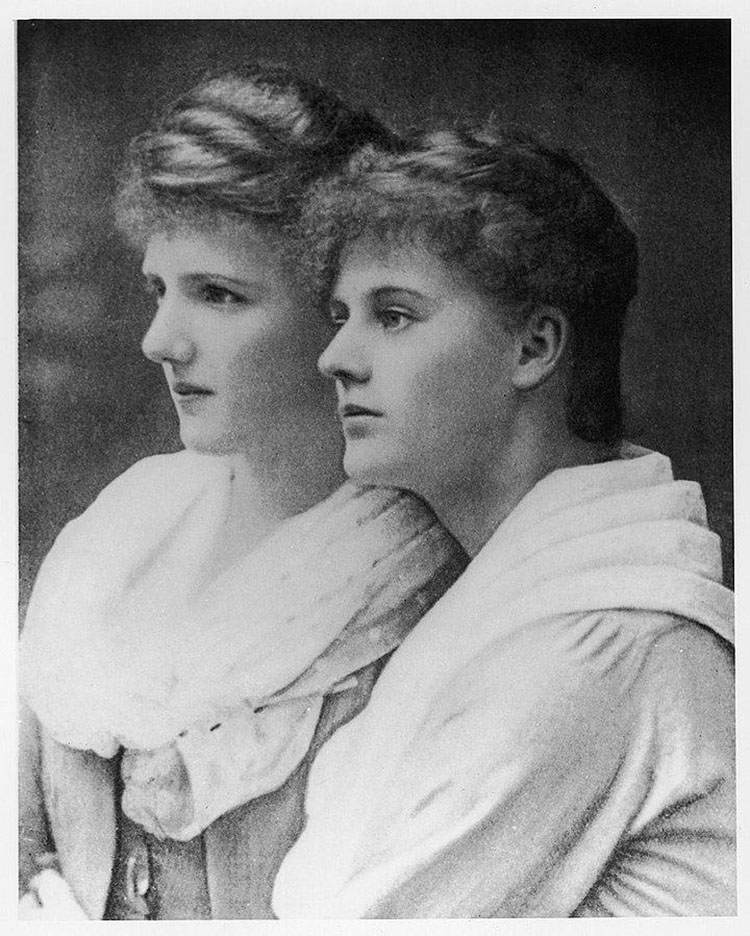

Those that are familiar with Markievicz because of her involvement in the 1916 Easter Rising may be surprised to learn that she in fact had an extremely privileged upbringing. Eldest daughter of adventurer and explorer Sir Henry Gore-Booth and Lady Georgina, she spent much of her childhood between London and the grand family home Lissadell House.

Her father’s compassion for others is believed to have greatly influenced Constance and Eva’s own social concerns and political ideals, especially during the Irish Famine of 1879, throughout which Gore-Booth ensured that his staff and tenants had access to enough food. This turbulent time in Irish history opened the Gore-Booth sisters’ eyes to the plights of the poor, and for Constance in particular, the struggles of the Irish under British rule.

It was not until she began studying at the Slade School of Art in London that Markievicz herself first became politically active, joining the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies in 1892. Following her marriage to Casimir Markievicz in 1900 and the birth of their daughter in 1903, the young family settled in Dublin, where the Countess’s particular involvement in nationalist politics became more prominent, joining the republican Sinn Féin party and radical women’s organisation Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland) in 1908 2.

During this time, Markievicz formed strong bonds with the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and the high-ranking members that became the driving force towards the 1916 Easter Rising. These included Bulmer Hobson, Thomas Clarke, Partick McCarten and Seán McGarry, to name but a few. Despite her official exclusion from the brotherhood as a result of her gender, Markievicz herself explains how the IRB ‘educated me and took me under their wing, explaining to me all the intricacies of such simple things as organizations and committees’ 3.

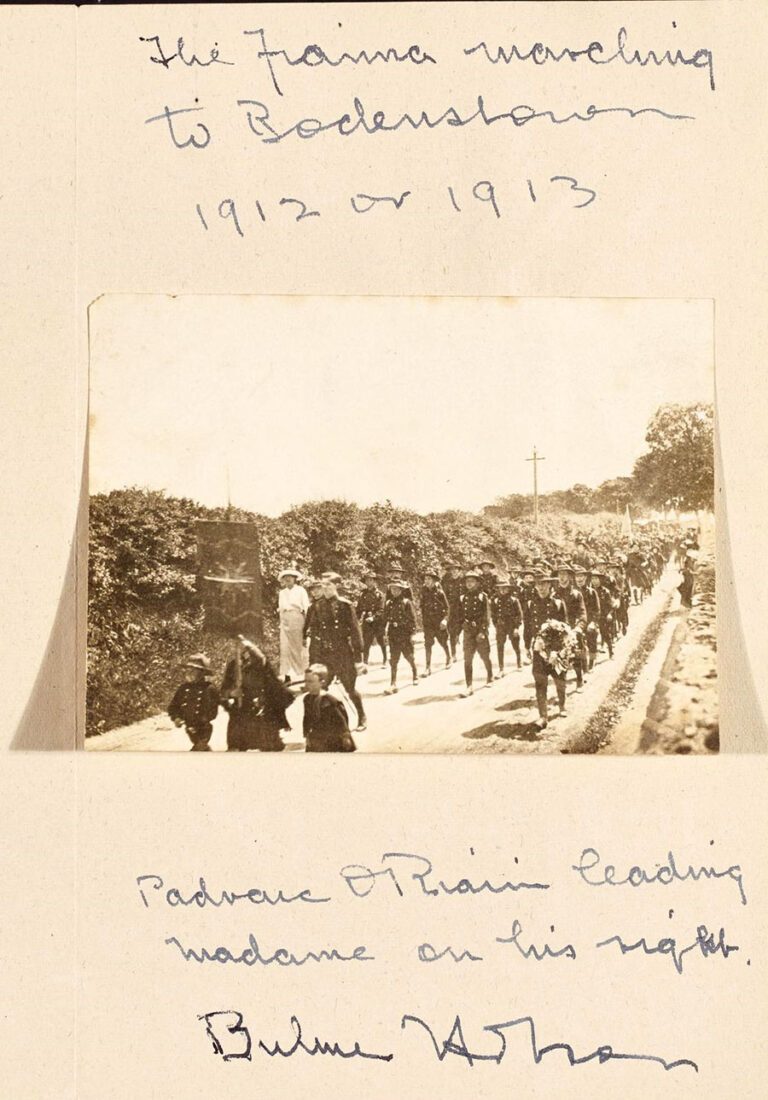

This revolutionary education inspired Markievicz to take a more active role in Irish nationalist politics. In 1909, alongside Hobson, she founded the para-military youth organisation Fianna Éireann and acted as the group’s President. The Fianna were actively involved in the Easter Rising of 1916 and sadly many young boys were severely injured or lost their lives in the fighting.

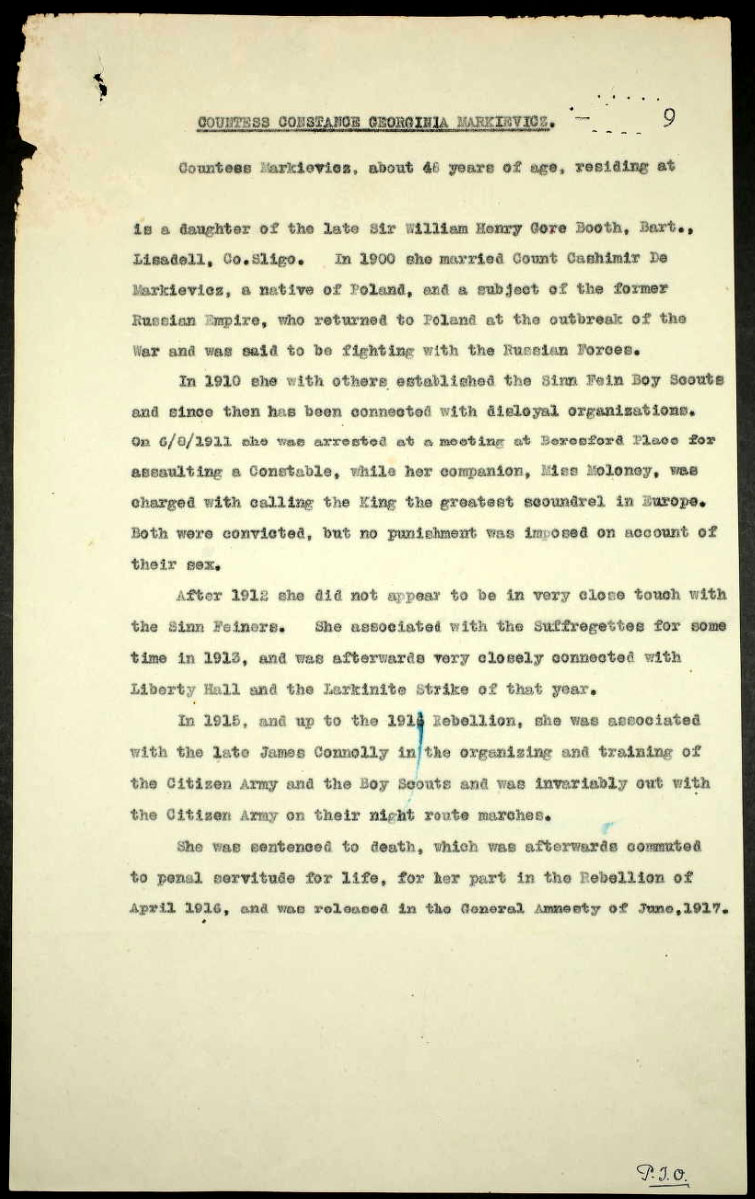

Over the course of the next seven years her position as a loyal republican and her devotion to ‘disloyal organisations’ became increasingly evident. She was arrested for the first time in 1911 along with Helena Maloney for their participation at an IRB demonstration, protesting against King George V’s visit to Ireland. Maloney was arrested for damaging images of the King and Queen, while Markievicz was arrested for successfully attempting to burn a Union Jack flag and injuring a policeman in the process. Documents reveal that ‘both were convicted, but no punishment was imposed on account of their sex’ (CO 904).

Documents also reveal that ‘in 1915 and up to the 1916 Rebellion, she was associated with the late James Connolly in the organising and training of the Citizen Army and the Boy Scouts and was invariably out with the Citizen Army on their night route marches’ (CO 904) 45. The Irish Citizen’s Army (ICA), a growing force of nationalist volunteers, formed during the 1913 Dublin lock-out to protect participants at anti-imperial and workers’ protests 6. In her biography Anne Haverty writes, ‘all her aspirations found a voice in this little army, the cause of Ireland, the cause of the people, the cause of women, and her thirst for action’ 7. As the ICA grew substantially in size, so did their violent encounters with the police. But this did not deter the group which was, like Markievicz herself, determined to see Ireland gain independence from Britain.

After many years of preparation, by 1915 the groups with which the Countess had been involved (Sinn Féin, IRB, Fianna, ICA) joined forces to make a momentous decision – on Easter Sunday 1916 they would lead a revolution against the Crown. The subsequent events known as the Easter Rising would change the course of Irish history and solidify Constance Markievicz’s place as an Irish rebel and revolutionary.

In the next blog post I will explore her involvement in the revolution itself, her subsequent arrest and imprisonment, the many more arrests that followed over the years, as well as her political legacy.

Notes:

Men of Harlech: The Secret Commandos2024-05-20 02:11

4 Ways Video Can Drive Traffic and Conversions2024-05-20 02:07

7 Post-Holiday Revenue Generators2024-05-20 01:55

5 Effective Online Marketing Tactics for 20122024-05-20 01:50

Mining Reviews for SEO Benefit2024-05-20 01:17

7 Post-Holiday Revenue Generators2024-05-20 01:13

Ask an Expert: How to Increase Conversion Rates?2024-05-20 00:54

3 Ecommerce Personalization Strategies2024-05-20 00:03

SEO: 8 Reasons to Stop the Addiction to Keyword Demand2024-05-19 23:50

Emphasize Key Details for Effective Product Descriptions; 5 Pointers2024-05-19 23:42

SEO Sidecars More Trouble than They’re Worth2024-05-20 02:06

Selling Luxury Goods Online2024-05-20 01:44

Can Spelling Mistakes Impact Ecommerce Conversion?2024-05-20 01:40

Ask an Expert: How to Increase Conversion Rates?2024-05-20 00:52

SEO Ranking Forecast: 74 and Sunny2024-05-20 00:43

Managing Google Product Feeds in Google Merchant Center2024-05-20 00:26

PetFlow.com: Customer Focus, Business Savvy Drives Success2024-05-20 00:22

Website Showcase: Designing With the Fold2024-05-20 00:21

SEO: How to Create a 301 Redirect Map, for Site Redesigns2024-05-19 23:48

Managing Google Product Feeds in Google Merchant Center2024-05-19 23:35